HISTORY OF THE FREE SDA MOVEMENT

|

CHURCH SEGREGATION RESULTS IN FREE ADVENTISM

|

|

| The first SDA church |

|

In the beginning

of the Seventh-day Adventist Church segregation was not accepted or

practiced in its congregations. Although its membership was

predominantly white, both white and black church members worshipped

together. Church history interestingly shows that even in the South,

where initially there were very few black converts to Adventism, it was

“the custom in pre-Civil War days [that] slave church members had

belonged to their masters’ congregations;” 1 in other

words, they both attended the same church. Unfortunately, however, as

more and more colored members began to be brought into the faith and

the racial climate got worse, church leaders began to adopt new

practices and policies, and people of color were denied equal rights

within the Seventh-day Adventist Church.

One observer who joined

the church at the turn of the 20th century and witnessed the gradual

changes in the church, was Elder John Manns, who shared his perspective

of the situation in these words, “About ten years the two races

experienced little or no difficulty in the North and West” as there

existed “equal enjoyment of religious rights and privileges,” however,

“as the denomination grew in popularity and influence, race prejudice

began to engender Negro proscription,” and when “the number of the

Negroes increased in the churches, race friction and proscription grew

more rapidly.” 2

The Spirit of Prophecy made it

clear that in some instances it was necessary for certain adjustments

to be made in different parts of the missionary field in order to

advance the truth. The church was instructed that these cautionary

measures be taken especially in those cases where “demanded by custom

or where greater efficiency is to be gained.” 3 These words

of wisdom and caution for flexibility in carrying forward God’s work

can be appreciated in light of the fact that it is “also a matter of

record in American history that in the 1890s, in a period of economic

and political unrest, segregation increased sharply, and many legal

restrictions date from that time.” 4

Although the

need for operating with greater caution under certain circumstances was

understood, church leaders often still tightened the cords of

segregation and inequality in circumstances where it was absolutely

unnecessary. Hence, those who were supposed to represent Christ and His

principles to all men sadly fell into the devil’s trap of exaggeration

and extremism by adopting a fixed policy on race relations.

“In

1890 Kilgore [a leader of the church’s work in the South] reported to

the General Conference Committee: ‘The work in the South for the White

population will not be successful until there is a policy of

segregation between the races.’ The policy, referred to by later

Adventist historians as the ‘Kilgore policy,’ was voted by the General

Conference in 1890. The segregation of individual Adventist churches

was now official denominational policy. Though this practice was, as

one Adventist historian put it, ‘shaped by policy rather than

principle,’ it eventually came to be taken for granted so widely that a

majority of Seventh-day Adventist members, particularly in areas in

which segregation was the custom, believed it to be a fundamental

teaching of the church.” 5

Despite the policy

adopted by the leadership of the Seventh-day Adventist Church, Ellen G.

White, the church’s prophet, nevertheless tried her best to point

leaders and members to the principles and teachings of God’s Word

regarding matters of this nature:

|

|

| Jesus' baptism and anointing by the Holy Spirit |

|

“There has been much perplexity as to how our laborers in the South shall deal with the ‘color line.’ It has been a question to some how far to concede to the prevailing prejudice against the colored people. The Lord has given us light concerning all such matters. There are principles laid down in His Word that should guide us in dealing with these perplexing questions. The Lord Jesus came to our world to save men and women of all nationalities. He died just as much for the colored people as for the white race. Jesus came to shed light over the whole world. At the beginning of His ministry He declared His mission: ‘The Spirit of the Lord is upon me, because he hath anointed me to preach the gospel to the poor; he hath sent me to heal the brokenhearted, to preach deliverance to the captives, and recovering of sight to the blind, to set at liberty them that are bruised, to preach the acceptable year of the Lord.’” 6

Although church leaders were fully aware of these counsels from the pen of Inspiration, they sought to implement their unChristlike policy everywhere, and not just in certain circumstances that existed in parts of the South. Nevertheless, many blacks saw light in the Three Angels’ Messages and still joined the Seventh-day Adventist denomination. Over the years, however, things got worse and several attempts were made by black SDA ministers to bring about necessary changes in church policies, but their efforts fell on deaf ears. Among those who sought to make such changes in the early years were Elder Charles M. Kinny, the first black ordained SDA minister, Elder Lewis C. Sheafe, Elder George E. Peters, Elder James K. Humphrey, Elder John W. Manns, and others. But as things worsened throughout the years, the situation eventually resulted in increased defections from the organized body as many colored members began to separate themselves from the church. Those who made attempts to bring about the needed changes were often inspired by the open rebukes against racism and segregation, coupled with words of hope, that were often uttered by Ellen G. White in her writings to the church:

“The Black man’s name is written in the book of life beside the White man’s. All are one in Christ. Birth, station, nationality, or color cannot elevate or degrade men. The character makes the man, if a red man, a Chinese man, or an African gives his heart to God, in obedience and faith, Jesus loves him nonetheless for his color. He calls him his well-beloved brother. The day is coming when the kings and lordly men of earth would be glad to exchange places with the humblest African who has laid hold on the hope of the gospel.” 7

Despite the efforts of black leaders and Ellen White to get church leaders to introduce necessary changes, “most white communicants [church members] appeared to be comfortable with a segregated worship.” 8 This state of things continued until many colored church members became discouraged as they saw nothing was being done to improve things. They were convinced that regardless of their efforts to turn things around, church “congregations were not likely to be greatly different from other religious groups in regard to the color line.” 9 As a result, many colored members left the established church. Some departed from the truth forever, while others left the church for a while and eventually returned when things eventually changed. Some retained their church membership, despite the existing conditions, in an effort to fight the racism from within. Others vowed to maintain the original faith but felt it necessary to separate from their former brethren in order to maintain their own sanity and faith, as well as that of others.

|

|

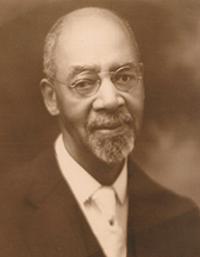

| Elder Lewis C. Sheafe |

|

Some very prominent black SDA ministers chose to take the last option mentioned above. Though they departed from the church structure, they sought to hold on to the faith. These leaders started self-supporting churches in different places, free from the control of the established body of the General Conference of Seventh-day Adventists. Among them were, Elder Lewis C. Sheafe, who pastored the First Seventh-day Adventist Church of Washington, D.C., the People’s SDA Church, and other churches, but later left and became pastor of the first Free Seventh-day Adventist Church, which was called, Berean Church of Free Seventh-day Adventists; Elder James K. Humphrey, the pastor of First Harlem church in New York City, which also broke away and became the United Sabbath Day Adventist Church; and Elder John W. Manns, who later left the body and became the founder of the General Assembly of Free Seventh Day Adventists. Thus, through these men historic or self-supporting Adventist churches were formed and Free Adventism was born. The members of this new movement soon began to be known by the name that they later adopted, Free Seventh-day Adventists. Thus, segregation resulted in the emergence or birth of Free Seventh-day Adventism.

It is this backdrop of neglect and injustice exhibited by church leaders towards those of their “own flesh” or of “one blood” (Isa. 58:7; Acts 17:26) that eventually gave rise to a series of exoduses from the established body. As a result, Free Seventh-day Adventist Churches arose in many different parts of the United States, the Caribbean, and Latin America (including Panama, Costa Rica, and Cuba). It is important to note that most of these separations occurred after Ellen White’s death in 1915, since matters involving the rights due to colored people in the church were not rectified until many years after she passed away. Among those self-supporting churches that arose shortly after her death was one whose foundation was laid in 1913 under the denomination but departed in 1916 (one year after Ellen White died). This church in Los Angeles California was called Berean Church of Free Seventh-day Adventists.

1. "Human Relations, Office of." Seventh-day Adventist Encyclopedia, Review and Herald Publishing Association, 1996, www.blacksdahistory.org/human-relations.html

2. Why Free Seventh Day Adventists, by John Manns, The Banner Publishing Assoc., Savannah, GA, 1920, page 5

3. Testimonies For The Church, Vol. 9, by Ellen G. White, Pacific Press Publishing Assoc., Boise, Idaho, 1948, page 208

4. Seventh-day Adventist Encyclopedia, Revised Edition, Commentary Reference Series, Vol. 10, Review and Herald Publishing Assoc., Washington, D.C., 1976, page 1193

5. Righteous Rebel, by W. W. Fordham, Review and Herald Publishing Assoc., Washington, D.C., 1990, page 67

6. The Southern Work, by Ellen G. White, Review and Herald Publishing Assoc., Washington, D.C., 1966, page 9

7. Ibid, page 12

8. We Have Tomorrow, by Louis B. Reynolds, Review and Herald Publishing Assoc., Washington D.C., 1984, page 302

9. Ibid

|

|